SUDAN

Deciding to go to Sudan surprised a lot of people. There is so much negativity around the name of the country in the press, and very few people know much about it. To be fair, I didn’t know much about it before I went. For all kinds of reasons it’s one of my favourite trips and I’d happily go back there.

My trip was exploring the ancient history around the Eastern Sahara known as the Nubian Desert in the north of Sudan. About 7000 years ago, It had been originally green and verdant savanna grassland and home to many animals such as lions and giraffes. It was also good pasture for cattle. Envious of the lushness, the Egyptians invaded Nubia and built temples and enslaved the people. After a few centuries the Nubians (or Kushites) turned the tables, became kings themselves known as the Black Pharoahs, and ruled Nubia and Egypt itself for a while. There is a definite Egyptian influence everywhere. The Nubians copied a lot of the art and architecture and there are more pyramids in Sudan than in Egypt. Climate change around 700BC meant the desertification of land was moving southwards, so the kingdom relocated further down the Nile around Meroe. Eventually the kingdom lost its power as the desert further encroached and nomads with desert-friendly camels took over their trade routes.

Arriving at Khartoum airport was everything I had hoped for – a massive shed with all kinds of apparent chaos, yet somehow our bags came out ok and we were out and into Sudan. I had joined a small group of eight. I’m not sure if you can travel here alone but I liked having company. We had an Italian guide, Denise, who had spent a lot of time in the country, and a Sudanese cook, Monim, and a couple of drivers.

One of the most famous things about Khartoum is it’s where the Blue Nile meets the White Nile, and so we went to see the point of confluence in what looked like an abandoned fairground. There are disputes as to where each rises but popular agreement is the Blue Nile comes from Lake Tana in Ethiopia, and the White from Lake Victoria in Tanzania. Afterwards my first taste of Sudanese food: lots of hummous-like dips and peanut/bean salads, grilled fish and meat and a minty lime drink which was very refreshing.

The National Museum of Sudan is a fine collection of art and statues. It’s not a sophisticated museum, there’s no shop/café/interactive exhibits. But it’s refreshingly unpretentious, and nearly everything in it was found in the country itself – no plundered treasures from around the world here (unless you count the Nubians in Egypt as colonialists). My favourite were the coptic wall paintings from Faras Cathedral which we weren’t allowed to photograph. The museum also houses two complete temples that were rescued when Lake Nasser was created. Below is a 2000-year-old statue found at Meroe where we were heading. She looks puzzled. Perhaps because she has no idea what the little figure next to her is supposed to be.

In the evening we had a sunset sail on the Nile itself. Khartoum is not a beautiful city, at least not from the river. But it does have some interesting architecture.

The next day, on our way out of Khartoum we stopped at the tomb of the Madhi leader. Sudanese history, like a lot of African history, is tribal and complicated, but essentially he had tried to break free from Egyptian influence in the 1880s and radicalise the country, but had been thwarted by an Anglo-Egyptian force, led by Kitchener, and some of the other Sudanese tribes. Kitchener had desecrated the Madhi’s body and bombed the tomb, but since then it has been restored and is well-maintained – there were even people working on the dome while we were there.

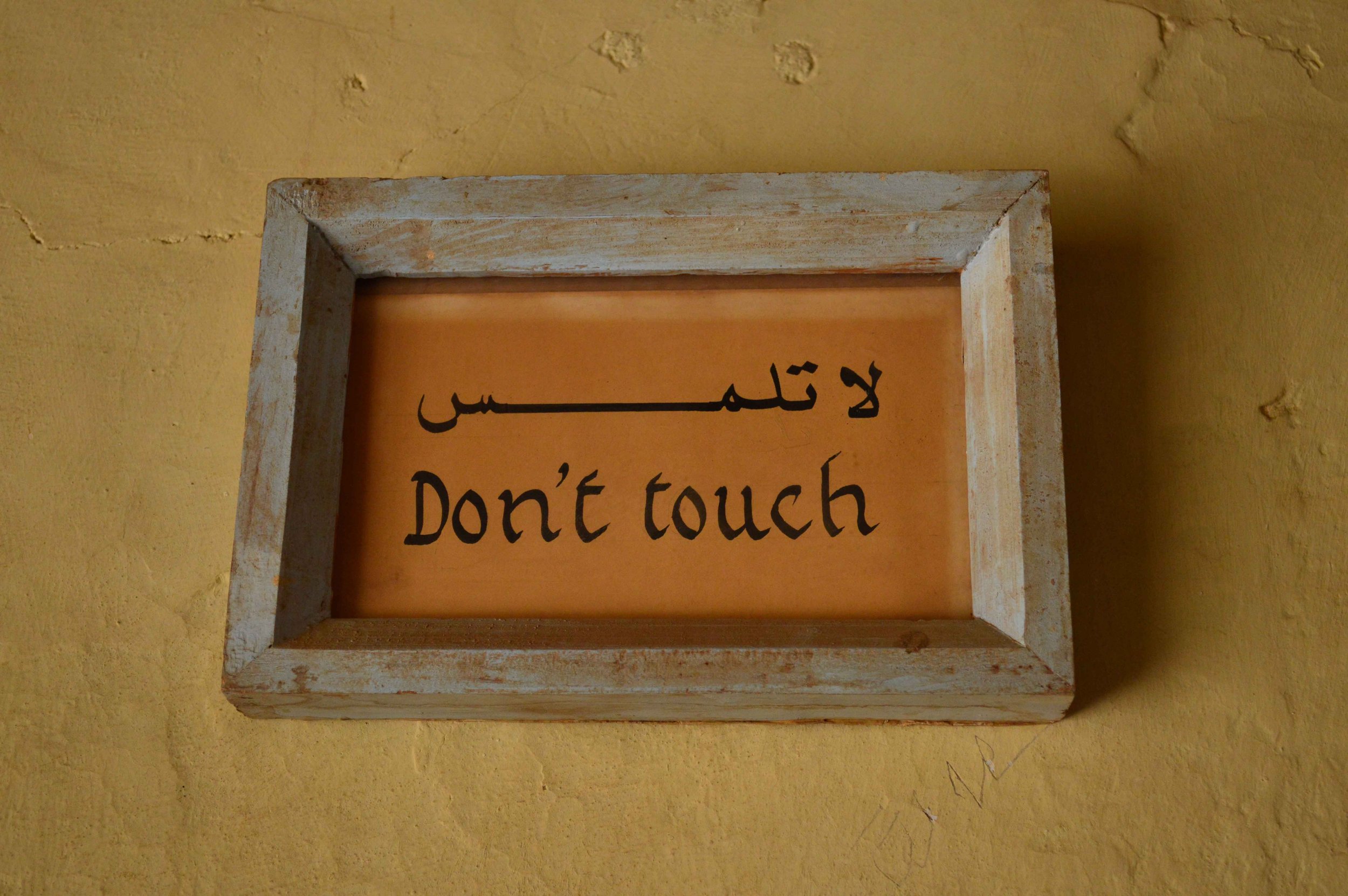

Across the road was the mudbrick house of the Khalifa who had also been an influential leader and Mahdi’s successor. The house is big and sprawling with a rabbit warren of rooms and corridors and courtyards and is now an ethnographic museum with lots of interesting artefacts on display, and a cupola from the original tomb out in the courtyard.

We headed up on the ‘northern lifeline’ road out of Khartoum. We had a toilet stop next to a huge pile of boulders which I assumed had been dumped there but apparently were there by erosion. There’s nothing like geology to make you feel insignificant.

Lunch was at a truck stop and we had some tamiya freshly made by our cook. They are falafel-like, made with chick peas, and very tasty. While we were eating a jeep pulled up and out got Chris Leadbeater, a travel writer I follow on Twitter. I had seen him posting pictures of Khartoum a couple of days earlier but even so I wouldn’t have expected to bump into him in a country that’s eight times bigger than the UK.

A little after we had set off, we suddenly took a sharp right and were now off-roading through the desert to find some of the hidden treasures, and it started feeling like a proper adventure. How the guys know where to drive is a marvel as there are no roads, signs, obvious features. They literally remember certain rocks or use their instincts based on previous trips.

We got to a place called Naqa where there once was a large city. Here stands a temple to the Egyptian god Amun, built by the Kushites, and guarded by a parade of rams. Nearby is the temple of Apedemak (Nubian god, head of lion, body of man) and what they call a ‘kiosk’ that shows elements of Egyptian, Roman and Greek styles, and looks like it is going to fall down any minute. Apedemak was now the principal deity for the Nubians, the Egyptian gods like Horus and Amun had moved down the pecking order.

You pay a small fee for entrance to both temples to the man who manages the nearby well used by the local farmers to feed their livestock. I say ‘farmers’ but the herders were mostly kids.

We drove to a wadi to make camp for the first time. I like camping anyway, but in the eastern Sahara it was very special. We each had a small tent to pitch – not the easiest thing to do in sand. Early evening the desert was still very hot but in the middle of the night it was freezing so you need more layers ready. Tempting as it was to pad through the sand in bare feet, we had to wear shoes because of scorpions who hide just below the surface, and we obviously had to be very careful if we needed the toilet in the middle of the night.

Each evening we built a big fire while our food was being cooked. Then sat around and ate and talked and watched so many shooting stars that we ran out of wishes to make. We had no wifi obviously, and no alcohol.

Luckily there were some interesting characters in our small group who kept us entertained. Vlado is a Czech writer and academic who had written about globalisation. He was fascinating – he has been everywhere in the world both as a teacher and on holiday. He told me it would be easier to tell me where he hadn’t been which amounted to about four countries (including South Sudan). His favourite place was Chad and he often took students there. He was in his eighties but was fitter than the rest of us put together. He had a wicked sense of humour and I was a little bit in love with him by the end of the trip. Sadly for me, his lovely wife was also travelling with us.

Then there was Peter, a law lecturer who travelled extensively as part of his job, but also as an amateur archaeologist and a lover of opera. I first noticed him on the plane out reading a heavy hardbacked book about Sudan. He brought only a small wheelie case and a brown leather satchel for the book but was immaculate the whole time we were there. Every morning he stepped out of his tent in clean chinos, an ironed shirt and a smart panama. One morning Vlado asked him if he had brought a valet with him. He was also very amusing, and made the trip a lot of fun.

Our camp was close to another Meroitic temple – Musawwarat es-Sufra so we walked there the next morning. It’s not quite as impressive as Naqa, but it’s still impressive. I was particularly taken with this elephant – there are quite a few of them about which suggests they were once prevalent here.

We then drove to Shendi (also called Shandi) which is a historic trading place and still has a decent-sized souk. We bought some very ripe melons – the fruit and veg were very impressive. Otherwise the souk was exactly as all markets are around the world: a combination of local produce and cheap tat. We got lots of stares, mostly friendly, and people shouted ‘Hello stranger’ at us which is the only English many of them know. It was odd that we were the main attraction when we were the tourists. We found a tiny café and had fruity tea and melon.

As we drove towards Meroe, we could see the pyramids come into view. They are taller and narrower than the ones in Egypt, with the tops knocked off by an Italian tomb raider called Ferlini who stole most of the treasures. But there are so many of them, it must have been so impressive when they were first built.

Our camp at Meroe was pure Out of Africa. We each had an old-fashioned style canvas tent furnished with antique furniture and chairs on the deck overlooking the pyramids. We had a bathroom unit each set further back. There were so few guests at the hotel so we virtually had this and the site itself to ourselves.

We went for a late afternoon walk around the pyramids and funerary temples. They were originally burial chambers for the Kushite kings and had contained all the usual treasures that are buried alongside. A couple have been opened up but they are empty, but there are some interesting bas-reliefs on the walls. The first thing that strikes you is what a bad state of repair many of them are in. Although they are still standing over 2000 years later, they are crumbling, and some are semi-collapsed. There has been some attempt to rebuild the caps of a few of the pyramids but I’m not sure this works. They desperately need money to preserve and maintain these treasures but the country has greater priorities. More tourism is an obvious source of revenue, although I’m conflicted as I loved being the only ones here too.

As we waited for the sun to set between two of the pyramids the wind started to pick up. The next thing we knew we were sitting in a mini sandstorm and we had to wrap ourselves in scarves. It added to the romance of the place although my camera was never the same again – every time I adjusted the lens after that there was a crunching sound.

A few of us rode camels back to the camp. Peter was an experienced rider so he led and set the pace which was admittedly a bit faster than I was used to on any animal never mind a camel. But I managed to stay upright and it was so wonderful riding into our camp on camels, wrapped in scarves, like something out of Lawrence of Arabia.

The next morning we visited a local school that the travel company supports. Improving education in the country has its challenges. Once adolescent, the girls are separated from the boys which means double the required teachers, and it’s hard enough to recruit any at all in Sudan. And some of the nomads object to their children being educated at all as they are needed to help with the livestock. Progress is being made however. We went into one classroom and the children were adorable. We were allowed to take photos but I couldn’t bring myself to do it, it felt too invasive.

Afterwards we went to look at some more historical structures – these ones even more crumbling. There is also archaelogical evidence of an extensive iron smelting works here which is thought to have been once one of the largest and oldest in Africa.

Atbara is a city that was once the centre of Sudan’s railway industry. Improved roads and union problems led to the decline of the use of rail for freight and, although there have been plans to upgrade the system, it’s not what it once was. There is, however, a delightful railway museum in the city in the remains of an old church where you can see old engines, coaches, tools and photographs. It might be my overactive imagination but the sign above looked like it had once been riddled with bullets. There was a party of school girls visiting at the same time and we did a mutual photo shoot for each other.

One of the most enjoyable parts of travelling around Sudan was meeting people who lived here. A lot of people are semi-nomads. Traditionally Bisharin nomads, they are now mostly settled in woven shelters where they herd animals. We visited Mohammed’s home and met his two lovely daughters who giggled and chatted and played with their phones like most kids do around the world.

Our camp that night was in a volcanic crater in the Bayuda Desert and the sand was almost black and very coarse. I had to find some big rocks to hold the pegs in. But it was very beautiful and the colour of the sand set off the orange of our tents very nicely.

In the Bayuda Desert, famous for its volcanic activity, is the Atrun Crater where the Bishari people collect salt to sell. We climbed up the next morning to take a look around and it’s so odd to see this patch of green in this otherwise dry, orange area.

We then headed off for Karima but stopped to meet some more nomads. When I got out of the car, I could see this woman wearing a beautiful blue dress fluttering in the breeze on top of a nearby hill. She motioned me to come over and she showed me round her small plot. Her name is Neema and this building is where she and her husband live, plus they have a shed and a pen to keep their animals in. They had had two children who had both died and were buried nearby.

She was very happy to pose, more than that, she was almost a professional about it. I noticed Denise gave her some money when we left. Afterwards, I spoke to her about this visit as I worried that we were being intrusive among other things. Denise told me that it is an arrangement that they have with the nomads to bring tourists to come and say ‘hello’, ask questions, look around and take photos in exchange for money. At the moment, there are so few visitors to Sudan so it’s manageable.

The pyramids at Nuri which have a more squat, Egyptian-style shape than the ones at Meroe. They are also older. We then made our way to Karima to see Jebel Barkal and the remains of the Egyptian temple and watch the sun set behind the ‘cobra’ pinnacle.

It was interesting to see archaeologists working at El-Kurru. Among the discoveries so far is the underground burial chamber of King Tantamani and I overcame my dislike of sub terra to go down and take a look. Incredible Egyptian-style wall paintings including hieroglyphs showing the King his way into the afterlife, and the spells he would need from the Book of the Dead.

The road disappearing beneath sand on our way to Old Dongola.

We went to have lunch with a Sudanese family in their beautifully decorated house. As well as giving us a delicious meal, they answered lots of questions for us. We were keen to know more about the scarification practice which used to be much more common but is now dying out. Originally it was part of tribal identification all over Africa, and considered a mark of beauty. But the scars are usually made during childhood and it’s risky medically if nothing else. It’s hard to not to be judgemental about this although this lady was proud of her marks. I found this article about the subject really interesting.

The large jars in the background hold and cool water. They are common all over Sudan including at the roadside and are usually made by hand by local women.

Old Dongola is a deserted city that was an important part of medieval Nubia, the Makurian state. The building above was originally the throne room for the Makurian kings, but was later converted to a mosque and was in use until 1969 when it became a historical monument.

Below are the mad-looking qubbas which are Islamic tombs from the 17th century.

Our last evening was spent at Omdurman where the al-Qadiriya sufis gather every Friday night to chant and pray. The order was founded by Sheikh Hamed Al-Nil and it is at his mosque that the event is held. Visitors are ‘welcome’ although I feel ‘tolerated’ is a better word as this is a special event for them, where absolute absorption is needed to induce a trance, and we were clearly bystanders who weren’t going to join in.

A couple of times we got some unfriendly looks, and one man raised a stick at me before laughing and walking away. I was mortified when the crowd circle started moving backwards but I hadn’t noticed, and I was momentarily alone in the middle. That didn’t go down well. But mostly it was joyful singing and dancing with colourful dervishes rousing the crowds into a spiritual frenzy. I chatted to a man next to me who asked me more questions than I asked him, including how old was my daughter and was she looking for a husband etc.

Afterwards we went for a meal at a Khartoum restaurant and I was genuinely sad this was the last night.

The journey home was mostly trouble free but by now I had a streaming cold. Peter ‘passed’ me into the BA lounge at Jordan to make the most of the free fruit juices and food there.

I have funny story about my trip out and back. Going out, we flew via Amman where we had to change and we had to have our hand luggage rescanned. The Jordanian officials who were x-raying my bag could see something suspicious and asked if I had a knife in there. I didn’t, so we agreed it must be something else like a pen or a comb and they let me through. On the way back, exactly the same thing happened – they could see a knife on the x-ray. This time they searched the bag, didn’t find anything and let me through again. Imagine my horror when I got home and found my swiss army knife at the bottom of the bag. I had no idea it was there. If I had, I would never have been able to deny it. Amazed, and concerned, that I got through Heathrow security with it on the way out.

I would definitely recommend Sudan to anyone who wants something different. It’s had its share of troubles, including very recently, and it’s unlikely to be on many people’s bucket list. But there is so much history here and the people are very friendly and many of them rely on tourism to make a living. A lot of the ancient structures are crumbling and need the cash boost that tour groups bring in. It’s unimaginable that heritage sites in most other countries would be allowed to deteriorate to this extent.