BHUTAN

I find it quite hard to write about my visit to Bhutan. It was an enormous privilege to be able to go to this tiny, ancient kingdom hidden in the Himalayas, but I was very ill while I was there which made me weak and tired and I didn’t have the energy to partcipate and enjoy the experience fully. But I did see some wonderful things, and I learned a lot about mountain life, and the nature of Buddhism, good and bad. It was also my first time in the Himalayas.

The Bhutanese work very hard to preserve their way of life and the environment in particular. This means keeping tourist numbers under control. There is a daily tourist levy and a traveller there has to have a registered guide. You are shown what they want you to see so there was a lot of focus on temples for example, but very little interaction with ordinary people. We weren’t allowed to wander around on our own and we followed the same circuit as other groups and regularly saw the same faces. I notice that even when independent travel evangelist Anthony Bourdain went there, he was on the same route with a guide. All this effort is designed to preserve its uniqueness, and, despite the restrictions, I felt this was mostly a very good thing.

Arrival into Bhutan is quite a thrill. Bhutan Airlines flies from India to Paro airport, and the plane has to weave through the Himalayas before turning sharply to land on a very short runway which can’t be seen until the last minute. There are only about 12 people in the world qualified to do it – luckily one of them was our pilot!

I had shamelessly flirted at the check-in desk at Delhi airport and secured a left-hand window seat so that I would get the best views of the Himalayas. I was sitting next to a lovely Bhutanese couple who flew this route regularly and were happy to point mountains out to me despite a lot of cloud. At one point we saw the summit of Everest poking out of the clouds and here is my award-winning photo of that moment.

As we descended, I could see lots of pretty temples nestled in the hillside. There was very calming flute music playing in the cabin – I am guessing not everyone was as excited about this dangerous landing manoeuvre as I was. Paro airport was small, but beautifully decorated like most buildings in Bhutan.

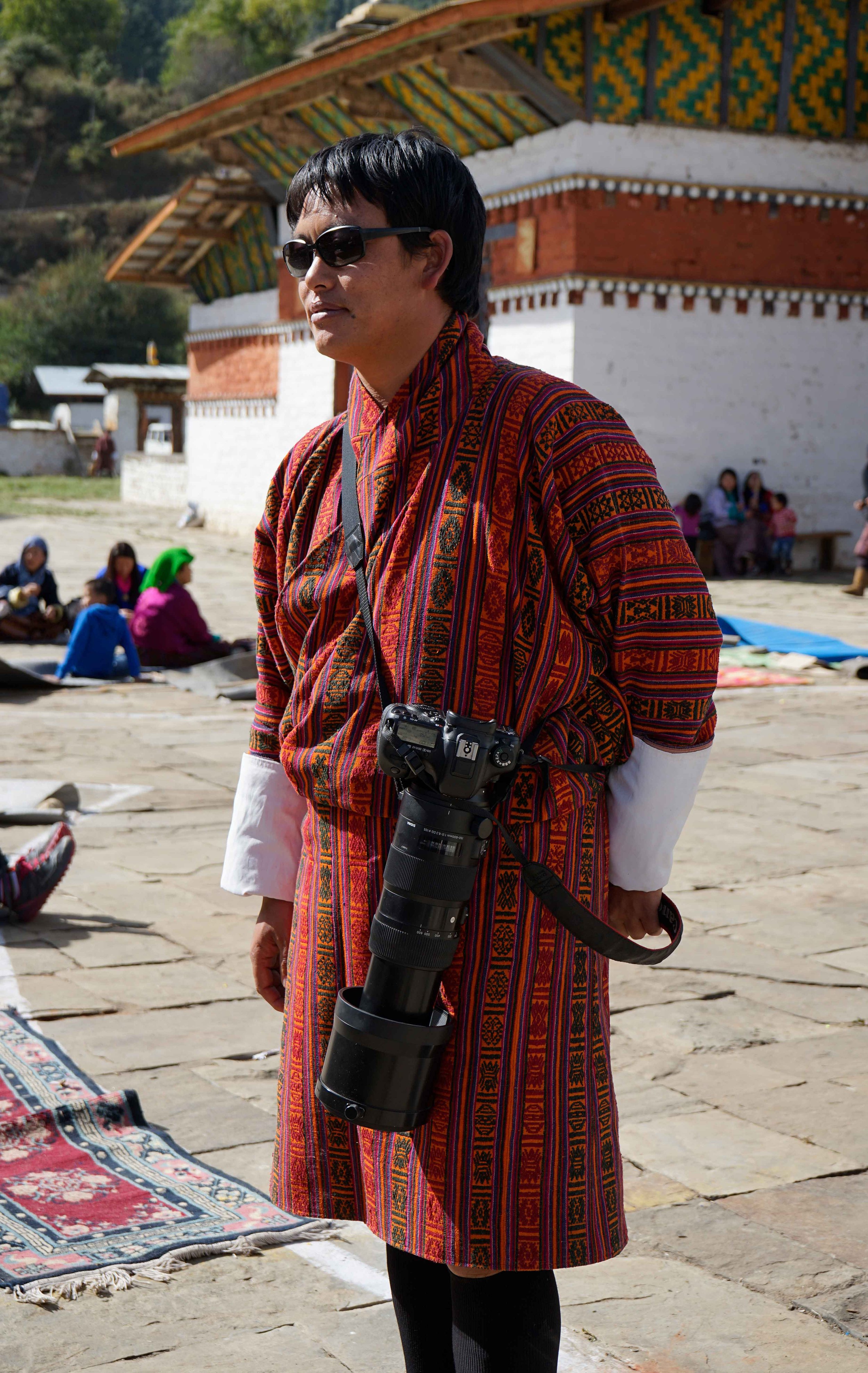

Outside our guide, Sonam, who wore traditional dress (gho) the whole time we were there, greeted us with khata. He was a great, he went above and beyond when I was ill – even talking about getting a helicopter to take me to hospital at one point. He was also a keen archer (Bhutan’s national sport), a budding photographer and a bit of a camera snob.

We drove to Thimphu and passed some hilarious road signs that said things like ‘Do you really want to die? Then drive slower!’ or ‘After drinking whisky, driving is risky’. Our hotel was in central Thimphu and, after a simple but tasty meal of vegetables and rice, I went to bed exhausted.

Overlooking Thimphu, is the giant Buddha Dordenma statue, bronze-cast and gold-gilded. Underneath is a temple full about 125,000 miniature versions of him, equally elaborate. It’s all very glitzy and flash and it cost a lot of money to build, but far more impressive is the devotion of the hundreds of pilgrims who come here to pray, and listen to the spiritual leaders speak. There are huge camps around the site where they can stay and some of them, like the family below, queue for a very long time.

Afterwards we went to the folk heritage museum is just outside Thimphu. I love places like this where you can see the traditional building methods used, and watch people practising crafts. Nearly all buildings are built using wood, including pine wood roof shingles, which is in abundance in Bhutan. A lot of the decoration on the wood is done by monks as a way of earning money for their monastery. I bought a bag of zao, a puffed rice snack roasted with butter and sugar, usually served with butter tea.

These young monks were at the Dechen Phodrang monastery, stunningly located overlooking Thimphu. It has been the tradition that families send a son, usually the youngest, to the monastery where they spend about eight years, or however long it takes to find enlightenment. These kids did look a bit bored and fed up which may be from having to answer our questions, but livened up when they went off to play football. I found it interesting that they all carried mobile phones tucked under their robes.

There is only one highway in Bhutan, the Lateral Road, that takes you west to east and back again. The road is basically a mountain ledge that occasionally drops into a gorge to cross a river and then winds back up again. In its current state, it’s quite terrifying. Occasionally I would look out my window at a sheer drop beside me, and the odd burnt-out wreckage down below.

It’s lucky the Bhutanese are devout buddhists as road rage is rare and accidents relatively few. Patience is also a useful quality as the road is being slowly upgraded. The only way to widen the road to make it safer is to cut further into the mountain. As it’s impossible to divert the traffic while this is being done, we periodically had to stop for an hour or so, while mountain rock was excavated and then the big rocks shovelled by a huge digger over the ledge on the other side. It was fun to watch but I was aware that it would take quite a few years to complete.

I enjoyed the drive through the beautiful landscape of Bhutan. I also liked the driver’s observation of quirky superstitions like driving twice around the stupa roundabouts prayer-wheelwise.

As we headed out from Thimphu we stopped at the Dochu La Pass home to 108 memorial chortens built in honour of lives lost during a flare up with Assamese insurgents from India in 2003.

The pass provides spectacular views of the Bhutan section of the Himalayas, with Mount Gangkar Puensum being the country’s highest at 7570 metres, but also the highest unclimbed mountain in the world. The pass itself is 3100m. There is a lovely semi-circular café with big windows that should look out on a spectacular mountain view, but there was a lot of cloud that day so the only view was a wall of whiteness.

We stopped at a traditional mountain home for lunch. They dry their colourful chillies on the roof and I saw these all over Bhutan. Below the most important animal in the country: the yak from which they get milk, meat, dung, fur and butter that they use for butter tea and for burning in lamps which apparently aids meditation.

The house was full of hundreds of dried chillies most of which will be used up making chilli cheese. Every dish is greatly improved by the addition of this Ema Datshi, a national speciality. If you ever go to Bhutan, and someone asks you if you want chilli cheese, just say ‘yes’. The dried green leaves are stirred into stews and salads. The food was quite simple but tasty.

We arrived at Gangtey in the Phobjika Valley. By now, I was very unwell but I was able to rest in a sweet little cabin. The stove looked like it was going to keep going all through the night but, like others I had in Bhutan, it was made from very thin sheet metal, and burned through wood as quickly as if it had been an open fire.

We had come here primarily to see the arrival of the black-necked cranes who fly in from China about this time of year. Of course they are not going to arrive on cue especially for me no matter how long I stood waiting with my camera. We were in the valley for two days and it was a no-show. We made do with a captive crane, who had been injured last year, and who looked just as anxious as I was to see the rest of them.

Meanwhile we were invited to watch the local school’s sports day to celebrate the King’s coronation. The Bhutanese love their royal family, their images are everywhere and you even see them driving around. (When the King had driven past us in Thimphu it was the most excited I had seen the normally-cool Sonam get.) The sports day itself was very sweet with the same sort of events you get in England, no egg and spoon race though.

Afterwards we walked through the valley and up to the Gangtay Monastery where I became a bit obsessed by Bhutanese doors.

Nesting birds had been here. Perfect for a swallow’s nest maybe?

Trongsa Dzong which for me was the most beautiful of all the buildings I saw. We went to the nearby Willing Waterfall restaurant for lunch and the food was the best of the trip, but I was too distracted by illness by now to enjoy it properly.

A long drive eventually brought us to the comfortable Bumthang Mountain Lodge Hotel. The next day we walked in the Chokhor Valley where the hope was we would see an abundance of wildlife. There are about 100 Bengal tigers in Bhutan, and about the same number of Snow leopards. The group was too noisy to see fauna of any kind, although we did find what looked like leopard paw prints and fresh leopard poo – we didn’t wait for it to come back to confirm this. Predictably, we didn’t see anything at all on the ground or in the air but I did like this tiny little rain shower on the hill opposite.

We spent the night in the Tang Valley at the home of a family who made us very comfortable in their big house and fed us well. Our rooms were simply furnished, and very cold, I spent most of our time here in bed trying to recover. It was the coldest night of the trip but luckily Sonam was able to score me a little heater.

The family were sweet. Typically, it is the women who seem to do all the work as is the case in so many countries. Below is Dorji (whose name means diamond in Bhutanese) showing off her version of chilli cheese which was one of the best I had.

The next day we set up to climb up to the Thowadra Monastery. I got a little way, and felt too weak to carry on. Reluctantly Sonam let me stay down by the river on my own on condition I didn’t wander off. Apparently the monastery was stunning, and I was disappointed not to see it, but I was also glad of a few hours of peace by the water and of course I did wander off a bit.

A highlight for me was the Jambay Lhakhang festival. The temple where it is set was built in the 7th century as part of a plan to physically restrain a supine and troublesome giant demoness who was lying across the mountains, and hampering the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet (Bhutan was part of the Tibetan empire at this point). This particular temple held down her left leg. Its construction, and its consecration by the Guru Rinpoche are celebrated each year by a four-day festival.

I watched about three hours of ritualistic dancing or ‘chams’ nearly all of which were performed by masked men. Each mask and dance has a special meaning and are overseen by the Gep Ap Atsara, a clown-like character who hovers around the edge. The only music was simple percussion which kept the rhythm. The dancing is quite mesmeric as they spin and dip and reminded me of the dervishes in Turkey.

I would have liked to watch more, and I wish I had had a better understanding of the meaning of each dance. But this event is for the Bhutanese people primarily, and I couldn’t expect them to provide me with an event programme in English. The festival culminates in a naked dance at midnight, the Ter Cham, which visitors are not allowed to attend.

I really cannot say what this guy is doing other than waving his ‘toy’ at the women and being given money to go away. I managed to dodge him thankfully although it wouldn’t be the last time in Bhutan I had an encounter with a man with a large wooden phallus. Later on that evening was the Mewang fire dance which is to bless women who believe they are infertile, and I imagine he takes part in that.

We spent a day walking the beautiful Punakha valley. Our starting point was on the other side of river of the dzong which we visited later. We climbed up to the Khamsum Namgyal chorten (Buddhist shrine) that had great views of the rice fields below. The colours were amazing – the golden crops, the turquoise melt-water river, the blue/green mountains.

This area is an important rice growing area in Bhutan and both red and white varieties are grown besides the rivers Pho and Mo Chu. We had got there for harvesting which is mostly done by hand including the threshing. These little ‘ricestacks’ are built to protect the unthreshed crop. There aren’t really any proper roads here yet so heavy machinery would be more of a hindrance than a help, many families keep a horse or a bullock for extra power.

The local families were friendly and smiley. We were allowed to visit one family in their home and, despite the healthy rice-producing industry in the valley, it was clear they were incredibly poor. I know they were given money to let us visit, but it’s another one of those instances where I’m not quite sure of the ethics of paying people to gawp at their poverty. I would have happily given them a contribution and not gone in the house.

We ate a picnic by the river and I dangled my tired, hot feet in the melted glacier water. Afterwards we visited Punakha Dzong (its Bhutanese name means ‘Palace of Great Happiness’) which is one of the most important in the country, and the site of the capital before Thimphu. It is richly decorated and I would have liked to have wandered around on my own a bit admiring the art. I was intrigued by the appearance of a conch shell motif in this tiny land-locked country. Fossils of sea shells have been found in the Himalayas from when this was the Tethys Ocean before the mountains were formed.

However, we had to stick close to the temple guide and he took us in about six different temples, shoes off/shoes on each time, and each temple having another convoluted story about Buddha and his family. I think you really need to be a true believer to appreciate the complexities of this religion. I’m only interested up to a point.

Everywhere you go in Bhutan you see phalluses painted on the walls of houses. The reason for this is credited to Drukpa Kunley or the Divine Madmen as he became known around 600 years ago. He rejected the monastic order and believed that licentious behaviour, including sleeping around, could still lead to enlightenment, and he and his ‘thunderbolt of flaming wisdom’ became legendary. Subsequently the phallus has become a symbol to ward off evil spirits and his temple a symbol of fertility. Many women have and still do travel there in the hope of being blessed.

I was nearly ‘blessed’ myself when I went to his Chimi Lhakhang temple. I noticed a man holding a large wooden phallus tapping some women on the head. ‘Don’t worry Lucy’ said Sonam, ’He will come and bless you in a minute too’. I couldn’t get out of there fast enough. Besides I already have kids so the last thing I need is a fertility blessing. Part of me wanted to laugh, but mostly I was just very embarrassed at the way something so ridiculous is taken so seriously. Or is it? I couldn’t work it out but the number of shops selling phallic souvenirs would suggest that many Bhutanese don’t either.

One of the last things I did in Bhutan was walk up to the Tiger’s Nest Monastery perched on a ledge outside Paro, 3120 metres up. The story goes that Guru Rinpoche flew here on the back of a tigress, landed on this ridge, meditated for a few years to clear it of demons, and founded the monastery. It’s very hard to find an alternative, more plausible story, so I’m willing to believe this is what really happened. The current monastery was built in 1692 but has been destroyed by fire as well as earthquakes a few times including as recently as 1998. As with most buildings in Bhutan, it’s built of wood, with butter lamps used as lighting internally, so fires are inevitable. Each time it’s been rebuilt, all the construction materials have had to be brought up here by foot or by mule – there are no shortcuts.

After missing out on an earlier monastery trek due to illness, I was now getting my energy back. I walked up on my own as I wanted to focus on my breathing and conserving my energy when I could – I was so determined to get there. It surprised me that I was allowed to do this, given the rules about having a guide with you at all times. The hike itself took me through the blue pine forest, and lots of water-powered prayer wheels and prayer flags tied to the trees. Every now and again I got a glimpse of the monastery. I passed schoolkids, tourists and pilgrims along the way, there was lots of people traffic. It’s a physical achievement to get to the top, but also a spiritual one, the only time I felt that while I was in Bhutan. I wandered around the monastery itself in a bit of a daze. After countless visits to temples, Buddhism had finally got to me.

So Bhutan was a mixed experience. It is definitely a very interesting country and it was mostly a positive experience for me despite being ill, but it didn’t feel like the ‘happiest country on earth’ as claimed. The concept of gross national happiness has been seized upon by tourist and marketing companies, who use it to entice visitors, particularly those with money who want to experience low-impact tourism and a colourful culture. But things are changing in Bhutan, the old world is having to get used to the new. Tourism, climate change and the internet are all having an effect on the country. The young in particular feel they are losing out as they compare their lives to kids in other countries. There are also alcohol and drug problems, high suicide rates, unemployment as well as instances of ethnic cleansing. These problems were not even talked about while I was there, not officially anyway.

It’s undoubtedly a beautiful place though, and unlike anywhere else I had been. I’m really glad I went while the country was still very traditional and largely unspoilt. It cannot last forever.